[Owl chatter is broadcasting tonight from a dumpy little motel on the outskirts of Albany, on the way to collect a promised hug from Susan in Vermont. The heat works, and the wifi, and it’s quiet — heaven!]

Residents of Crossworld know that ORR is either Bruin ice hockey great Bobby or, less frequently, Yossarian’s tent-mate in Catch-22. That latter ORR had no first name in the novel, but was Ivor ORR in the mini-series. In any event, as far as I can tell, it’s never been Louis ORR, who played pro basketball for the Knicks from ’82 to ’88, after excelling at Syracuse. He died last Thursday at age 64. In my house, he’s best known as head coach at Siena College in upstate NY, where Linda went! In his one year there, he led the Saints to a 20-11 season and a three-way tie for first place in their conference. He moved on to coach at Seton Hall and Bowling Green.

Orr was 6′ 8″ but weighed only 175 (ridiculous), so he was careful to avoid overly physical play when he was in the NBA. He scored over 5,500 points in his pro career, including a game-winning three-point shot against the Celtics as time expired on Jan. 20, 1987. He was inspired to become an evangelical Christian by a sermon of Jimmy Swaggart’s, and saw coaching as a kind of ministry. He wrote verses on the back of his game plans. His favorite: “For I know the plans I have for you,” declares the Lord, “plans to prosper you and not to harm you, plans to give you hope and a future.”

Amen to that, Coach!

The Orr in Catch-22 would sometimes stuff crab-apples in his cheeks. Or horse chestnuts. He also held rubber balls in his hands and when anyone asked him why he had crab-apples in his cheeks he’d show them the rubber balls and explain that they are not crab-apples, they are rubber balls, and they are not in his cheeks they are in his hands. He thought that was a good story but was not sure it got across well because it’s hard to speak clearly with crab-apples in your cheeks. Yossarian once asked him why he had crab apples in his cheeks and he said because they are better than horse chestnuts. When Yossarian blew up and asked why he had anything in his cheeks, Orr said “I don’t have anything in my cheeks — they are crab-apples.”

What perfect nonsense! We can only dream of attaining nonsense that pure. We miss you Joe.

I enjoy reading the comments on the day’s NYT puzzle that are posted on Rex Parker’s column. On many days, they are just random notes on how people did with the puzzle. Sometimes there’s a gem or two — some of the folks are very funny. I’ve already stolen material liberally from LMS, a teacher of problem children who’s a brilliant and amazing woman.

I’ve noted how little things in the puzzle sometimes open neat little doors for me — for example, who would have known about the Brazilian Butt Lift had not the puzzle used BBL in a recent grid? And sometimes people are moved to tell stories.

Today’s puzzle asked what fruit was used to make slivovitz. It’s PLUM. It opened doors for two stories:

My cousins in Poznan gave me a bottle of Slivowitz once. They distilled it from plum wine made from the plums in their orchard. The orchard in which their grandfather had buried their valuables when the Germans were coming in 1939. They still dug the occasional hole back there, on a slow day, hoping to luck onto more valuables. They gave my mother one of the valuables once, a scapular which was a sizable piece of thick metal which would have stopped swords and bullets quite well if worn on the breast. They thought it was medieval but an art historian friend said it had phony rivets on it, it was a 19th century tourist trinket. But back to the plum brandy. I used to sip a thimbleful of it every Christmas Eve and think of the Polish relatives, till I had a drunk over for Wigilia one year and he decided based on the taste that it was cheap rotgut and swilled the rest of the bottle in about 3 large gulps.

Here’s the second one:

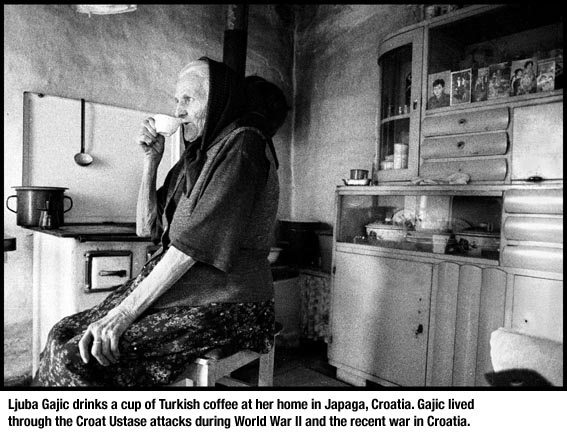

My first experiences with slivovitz/slivovica came back in the mid-90s when I took a year off from college to roam Europe, ending up for several months on a grassroots post-war reconstruction project in Pakrac, Croatia. We worked a lot on the Serbian side of town (the UN peacekeepers had left by then, so there was an understood border between the Croat and Serb sides that the internationals could cross without hassle). One morning, we walked over to Ljuba’s house to chop some wood. Ljuba was in her 70s, and lived not just through this war, but the horror of WWII. Despite her thin, frail appearance, she was still strong physically and mentally. She damned well would have chopped her own wood if we weren’t around. She greets us with shots of slivovica (which we just called “rakia”) and demitasses of Turkish coffee. Mind you, this is 9 a.m., and we’re starting the day with shots of seriously strong coffee and seriously strong spirits before we go out to wield a sharp axe for an hour or two. But this was hospitality.

I developed a fondness and palette for the drink. Every Wednesday, there would be a morning market near the town center and, among your standard provisions, there would be around six to eight vendors selling their homemade slivovitz. With free samples. Once again, bright and early in the morning. You could wander from stall to stall and get seriously blitzed by noon. But, with the sampling, you quickly learned the nuances of slivovitz and who made it well, and who just made awful rotgut. The flavors ranged from the unsweetened essence of Damson plums to odd off-flavors of soil and leaves. A trick was to dip your finger in the slivovitz, rub it on the back of your wrist, wait a moment, then take a whiff, as if you were testing a perfume. If it smelled of fruit and nothing else, it was good.

I found one vendor near the graveyard who had the reputation for having the best slivo in the area. On my way back to the UK and then the US, I picked up three two-liter Fanta bottles of the stuff for presents and personal consumption. Customs didn’t seem to care. My uncle (from Zakopane, Poland) loved the stuff so much, I gave him an entire bottle. He swore not only that it didn’t give him a hangover, but that he even felt better the next day after drinking it, as if it were some sort of elixir.

Three years later, I found myself living in Budapest. One of my fellow volunteers, a Kiwi named Jackson, came through town and stayed at my place for a month. His mother had just passed away, and he was backpacking across Europe to process his loss. In a bit of youthful spontaneity, we decided to rent a car and revisit Pakrac with a couple colleagues of mine. Part of the visit was impelled by the news of the death of Ljuba, whom we wanted to pay our last respects to at the graveyard. Part of it was for Jack. We arrive, find the graveyard and the austere plot, and say a few words. As I left the graveyard, I remembered the slivo, and I hoped I remembered the house. I approach the door, knock, and mumble the best of my half-remembered Serbian to say, “um…[mismo bili volonteri] we were volunteers here three years ago, we think we bought some rakia here, do you have any?” A blank face stared back at me, then a wave of comprehension, and a big smile. “Come in, come in! How much do you want!” We were sat, fed, and, of course, served shots of slivo. We talked about the town, how post-war life was progressing, all in my broken Serbian, and the understanding was though life was tough, things were getting better and people were tired of the tensions.

When I have a shot of slivo these days and taste the burning plum liquid slide down my throat, all of those feelings and memories fill my spirit.

He ended by sharing a link to this photo of Ljuba:

Oooh, it’s almost eleven and I have to make it to Middlebury by 1 tomorrow. And who the hell knows when I’ll grade the damn tax exams. They can wait. Thanks for stopping by!